My Love-Hate Relationship With the Word "Resilience".

Too busy to read or prefer audio? Listen to the audio version of this blog, below. Now available on my Spotify podcast.I love to hate you,

Hate to love you yet need you,

Resilience, my dear.

- a haiku about resilience

If Resilience and I were a couple, our relationship status on Facebook would state, “It’s complicated!” It’s complicated because we are in a constant flux of breaking up and making up, but we also cannot seem to exist without each other. I have written this blog three times, and with every iteration, I felt an increasing confusion towards resilience. Like ‘The Persuaders’ said, it’s indeed a thin line between love and hate regarding my relationship with resilience.

Why I Love Resilience

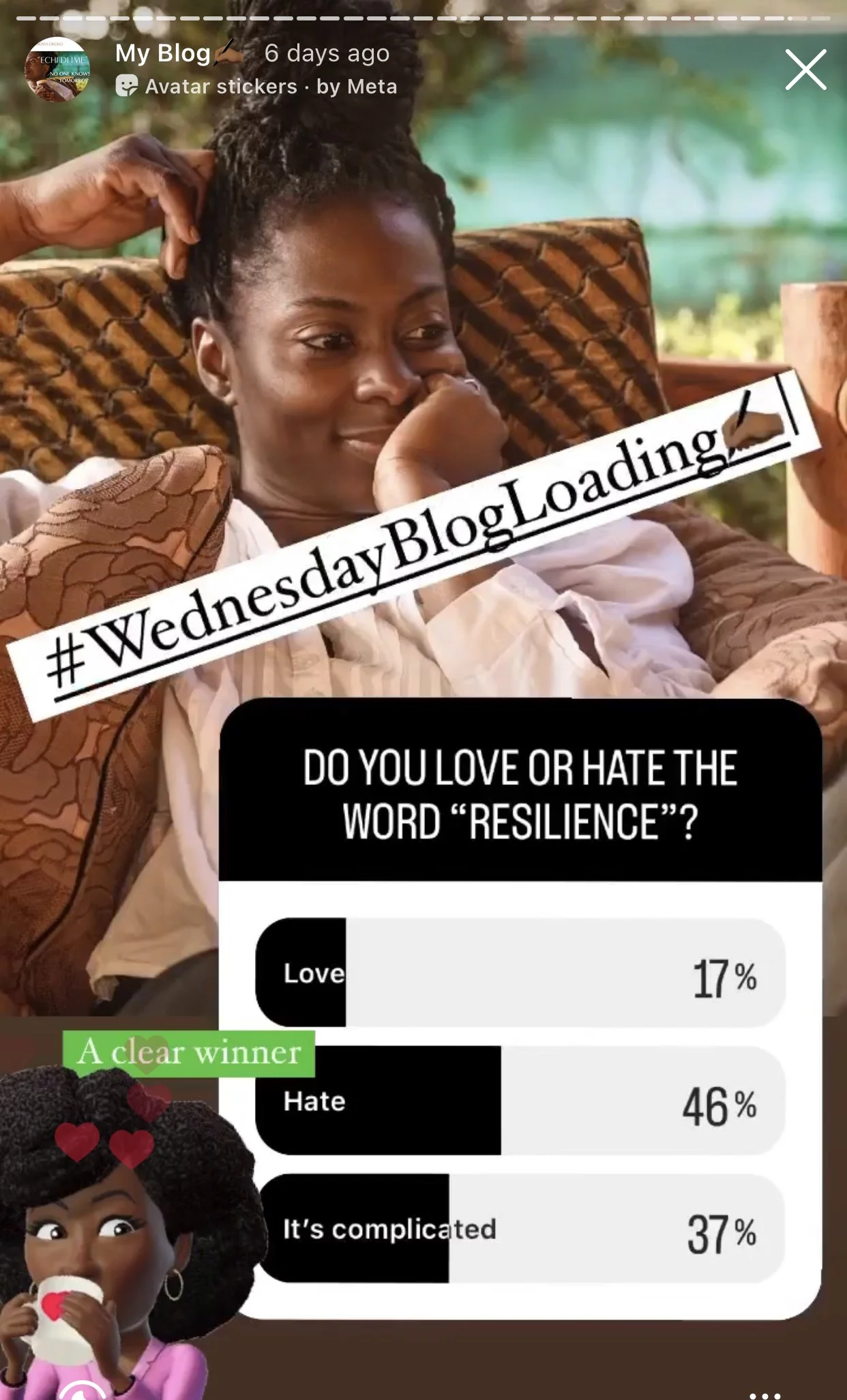

When asked whether they love or hate the word ‘resilience’ in a social media poll, 37% of people said “It’s complicated”

Because without it, I would not be who or where I am today. The highlights of my life reveal someone successful in many areas; however, I’ve had my fair share of adversities (rejections, incivility, failures, epic mistakes, burnout, disappointments, etc) that have critically shaped my path today. Peaks and troughs, as my sister Nomis calls them. I would rather never have experienced any of these. I keep chasing the soft life, but it keeps running away from me.

Medicine is a marathon, not a sprint. I have previously compared medical training to elite athletic or military training- they differ physically, but the mental rigour required to survive and thrive is similar. The long shifts and decades of training are merely the tip of the iceberg. I sometimes marvel at what I do for a living and how most of the world will never experience or understand what it is like to witness the most vulnerable points of people’s lives daily; to resuscitate, excise, cauterise and triage to heal. Sometimes we heal by doing nothing. Sometimes we heal by holding our patients’ hands and supporting a dignified death. Our actions are based on occasionally difficult decisions at difficult times, frequently with limited resources.

Drawing on detective skills using anatomy, physiology, pharmacology and sociopsychology to put together a differential diagnosis and treatment plan: to prescribe medications with known side effects with the belief that they will do good and cause minimal( or no) harm; to pull out babies stuck at caesarean birth or an impacted shoulder with the awareness that every second of oxygen is precious; to control major bleeding following a ruptured ectopic pregnancy in a woman who has already experienced multiple pregnancy losses; to review fifty patients in emergency department without a toilet or lunch breaks because you know they have waited five hours to be seen; to hold a patient’s hand whilst they die alone with no family or friends; to utter the words “ it’s not cancer” and experience shared relief; to break the news “I’m sorry it’s cancer” and hold space for despair; to assist the birth of a baby conceived after multiple failed rounds of IVF; to look a family in the eye after conducting an ultrasound of their precious baby and say the words “ I’m sorry but I cannot see a heartbeat”; to care for patients who have physically tried to assault you two hours ago; to apologise because we made a mistake we know may have been avoided if we had more time, training, staff or rest; to relish in the simple joy of delicious slice of NHS buttered toast at 3am on a night shift.*Sigh* #IYKYK

We do all these things, then go back to our family, friends and lovers and talk about the latest episode of “ Black Mirror” and our plans to see Burna Boy’s concert over the weekend whilst chopping up tomatoes to make jollof rice. The degree to which health workers can(must) compartmentalise work, and life is incredibly weird. We do it because we love the profession( mostly). We do it because we must get through the shift. We do it because we are trained to. We do it because we are resilient.

Why I Hate Resilience

I have often heard resilience being compared to being like a malleable rubber band. When placed under immense pressure, the band stretches, maybe never returning to its original shape but never breaking. Which material on earth can withstand indefinite stretch and strain? Is the aspiration for individual resilience in the face of chronic stress and strain realistic when we know that resilience, like willpower and self-control, are finite resources? Arguably there is a fine line between resilience and normalised maladaptive behaviours to chronic stress. Resilience can very quickly evolve into or be masked as apathy, indifference, quiet quitting, burnout, incivility, and hypervigilance.

I keep chasing the soft life, but it keeps running away from me. I reject the title ‘Strong Black Woman’- tufiakwa!

Resilience is occasionally weaponised in healthcare settings. I have heard of junior doctors, nurses and midwives being offered “resilience training” when they have struggled emotionally or physically following significant adverse outcomes, resitting professional exams or dealing with chronic rota gaps. Some colleagues refer to the younger generation of health workers as “snowflakes” because we do not cope with (or rather refuse to tolerate) the working conditions that our predecessors accepted and normalised. This is a shame but not a surprise. In times of stress, empathy is often the first thing to disappear. We pay more attention to building resilient people rather than resilient systems and environments that do not run by burning the finite fuel of goodwill, willpower and resilience of hardworking but overworked individuals.

Endurance is the Near Enemy of Resilience

I recently learned of the Buddhist concept of ‘near enemies’- emotions or traits which masquerade as positive virtues or values but actually arise from a different and sabotaging space. For example, pity is the near enemy of compassion, and attachment is the near enemy of love. Is endurance the near enemy of resilience? Perhaps the problem is the definition of resilience I’ve been sold. The kind that requires you to be tough, thick-skinned, be able to endure indefinitely and have a camel’s bladder. Perhaps like me, many of you have mistaken endurance for resilience when the truth is you can be an absolute ‘snowflake’ and still be resilient! The (un)fortunate truth is that we cannot survive or thrive without resilience. The ability to bounce back from setbacks and the strength to grow through adversity are vital components of a resilient mindset. Bouncing back requires self-awareness, softness and ease. By embracing the delicate balance between recovery and strength, we can practice healthy resilience as a way to face life's challenges head-on, adapt to change, find strength in vulnerability, and emerge from hardships stronger, wiser and softer.

Personally, I’m unlearning the lies I have been told about resilience and embracing a new definition that centres on growth, self-awareness, authenticity, healthy boundaries, and soft fluffy edges. To do this, I have had to learn the difficult but liberating concept of self-leadership and explore my ikigai, which I have written about in previous blogs. I’m still very much a work in progress.

My Recipe for Resilience

2 parts curiosity

2 parts staying hydrated and moisturised

Heaps of “healthy boundaries”

A sprinkling of growth mindset

A dab of good humour

As much sleep as possible!

My take-home message is to continue to moisturise your soft fluffy edges.

Writing this in the backdrop of the junior doctors’ strike and celebration of the NHS 75th birthday is apt. I support my colleagues on the picket lines and am proud of the NHS. I chose to study medicine in the UK because of the NHS. As a teenager growing up in Nigeria, I was blown away to learn of a healthcare system founded to provide free care to all at the point of need. Universal Health Coverage is a human right that I will continue to fight to uphold.

I am proud of the NHS because it is propped up by amazing, talented, hardworking ( and resilient) people who show up. But I know we can and must do better. NHS workers deserve to be valued, nurtured, and adequately renumerated because we are worth it. Our patients and service users deserve to be cared for by the best.

Happy 75th birthday to the NHS!