C- Sections Vs Vaginal births: are all births are equal?

The content of the blog does not constitute medical advice. It is not intended to substitute for independent professional midwifery, nursing or medical judgment, advice, diagnosis, or treatment based on your circumstance.

Let me start out by stating that views on caesarean sections are like the Nigerian food amala, the condiment Marmite or Donald Trump. It is a topic that is truly polarising.

Over the next few minutes, I will explore the polarising force of caesarean sections and share some of my truths as a birth provider, obstetrician and gynaecologist. Grab a cup of tea.

What an honour to assist with the birth of this beautiful baby. Photo shared with permission by his wonderful parents.

This month I performed my one thousand four hundred and “something-th” caesarean section. Acknowledging this at this point in my career was significant for me. Obstetrics and gynaecology training lasts for seven years. I have taken two additional years to complete a fellowship, research and masters degree at Harvard, thereby extending my training to nine years. I’ve attended over two thousand births during this time.

In the UK, we have a midwifery-led care model. Obstetricians support this model by providing antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal care for pregnant people with medical conditions, previous complications and emergencies requiring assistance with medical interventions, instrumental, caesarean and occasionally spontaneous vaginal births.

On the morning before a recent elective caesarean section list, I bumped into a woman who needed directions to the hospital. We got talking and realised we were both from the same region of Nigeria. When she learnt that I was a registrar soon to become a consultant, she broke into praise and a beautiful prayer for me, my team and the pregnant people and babies we would be looking after that day:

As you draw to a finish, recognise this is a new beginning. When your feet tire, may our spirit carry you over the line. May your enemies never see your path. You will live up to your name. You will not only finish well, but you must finish strong so that people behind you know it is possible and continue to aim for more.

To which I responded, Isé (translated from Igbo as “let it be so” ). There are few things more powerful than the prayers of our elders and ancestors. If you know, you know.

Caesarean section birth is common.

Caesarean sections are the single commonest surgical procedure conducted globally. Did you know that some of the earliest recorded successful caesarean births where the mother and baby survived occurred in Central East Africa?

Sketch of a Caesarean Birth in Uganda in 1879, by Robert W. Felkin( Missionary Doctor) in Edin. Med. J. 1884.

Felkin lectured the Edinburgh Obstetrical Society on January 9th 1884, entitled “Notes on Labour in Central Africa”. He described a caesarean birth where the mother was comfortably sedated using banana wine; the mother and baby survived and made a good recovery.

Today 1 in 5 babies around the world are born by caesarean section. Whilst there is wide global variation, the overall trend is an increase in the number of caesarean births in all regions of the world, as illustrated in the maps below.

There is evidence of the inappropriate overuse of unnecessary caesarean sections in maternity care globally. Equally, in some regions of the world, it is underused, with pregnant people and their babies being denied access to a life-saving and preserving procedure. This phenomenon is often referred to as too much too soon, too little too late.

How do we get this balance right?

These maps illustrate that the highest regional caesarean section rates occur in Latin America, the Caribbean and North America, and the lowest rates in Sub-Saharan Africa. Betrán AP, Ye J, Moller A-B, Zhang J, Gülmezoglu AM, Torloni MR (2016) The Increasing Trend in Caesarean Section Rates: Global, Regional and National Estimates: 1990-2014. PLoS ONE 11(2): e0148343. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0148343

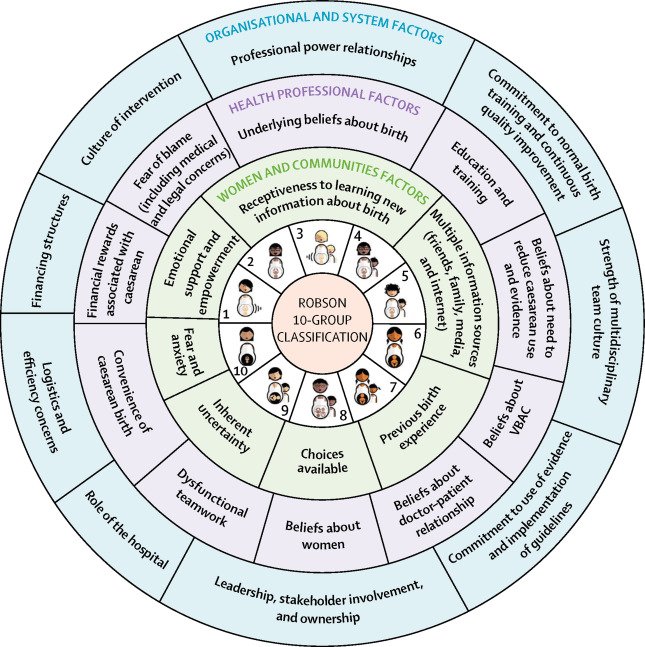

Multiple factors drive variation in caesarean section use. In 2018 a Lancet publication broadly classified multifactorial drivers of caesarean use into three groups:

This diagram illustrates factors related to pregnant people, society, health providers, and healthcare organisations that affect the frequency of caesarean section use at the local level; these factors surround the obstetric and clinical factors that also affect the frequency of births by caesarean section, which are represented in the middle by the Robson 10-group classification. Betrán AP, Temmerman M, Kingdon C, et al. Interventions to reduce unnecessary caesarean sections in healthy women and babies. Lancet. 2018;392(10155):1358-1368. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31927-5

Pregnant people and communities factors, e.g., maternal request, previous birth experience, choices available, emotional support and empowerment, fear of birth.

Health professional factors (midwives, doulas, nurses, obstetricians, anaesthetists), e.g., beliefs about birth, education and training, teamwork, fear of blame & litigation, financial incentives, and beliefs about doctor-patient relationships.

The organisation and systems factors, e.g., workplace culture, financing structures, logistics and efficiency, leadership, stakeholder involvement and ownership, the culture of intervention, commitment to training, quality improvement, research, and guideline use.

Caesarean sections save lives but also have risks.

Risks and benefits of Caesarean section described in RCOG patient information leaflets; designed by @isi_desisgns

Caesarean sections can be lifesaving and improve quality of life when done at the right time, in the right way, for the right pregnant person and/or their baby. However, it is critical to recognise that a caesarean section is a major surgical procedure. Complications such as bleeding, infection and pain are common. Serious complications like severe life-threatening bleeding and infection, though relatively less common in the UK, are leading causes of maternal deaths globally. The benefits of a caesarean section must be weighed against short, medium and long-term risks to the pregnant person and their baby and personal choice( see infographic- exploring caesarean birth).

In addition to complications, in lower-resource and austere settings without universal health care, the inappropriate use of caesarean sections places financial burdens on the pregnant person and their family (out-of-pocket payments, debt, financial toxicity) and restricts access to maternity beds, critical care, theatre services, blood banks, anaesthetists etc., for other service users.

What constitutes a high or low caesarean section rate?

It depends. There is a stronger push to move away from the previous practice of having targets for caesarean section rates. Historically, the WHO recommended population-level caesarean section targets of 10-15% based on the previous consensus that rates below this were associated with higher deaths in babies and pregnant people ( neonatal and maternal mortality) and therefore represented an under-provision of a life-saving procedure. Rates above 15% were not associated with improved outcomes for pregnant people and their babies. Since 2015 however, the WHO updated its recommendation for needs-driven rather than target-driven caesarean section rates.

Does a caesarean section rate of 20% sound high or low to you?

What does a caesarean section rate of 20% actually mean- other than 1 in 5 babies born in that specific population ( geography, time, demographic characteristics etc.) were born by caesarean section? What percentage of those were done electively or as an emergency? What proportion of them occurred in people who had had previous caesarean sections? What proportion occurred in people who requested a caesarean section in the absence of a medical indication?

What are the consequences of low or high caesarean section rates?

What does a caesarean section rate of 20% mean for pregnant people, their babies, workforce capacity, hospital resources and wider society in six to twelve months or even ten years? Without understanding the reasons for the caesarean section, the characteristics of the pregnant people, the hospital facility, the workforce and outcomes for pregnant people and babies, I don’t think a caesarean section rate in isolation is particularly helpful. Trends and context are more important.

National caesarean section rates mask variation between facilities and within populations.

In 2022, Scotland's national caesarean section rate was 37.6%, meaning that 1 in 3 babies born in Scotland was born by caesarean section. Within the Scottish population, pregnant people who are Black, older and from a higher socio-economic class experienced the highest caesarean section rates. In 2022, regional caesarean section rates across NHS boards ranged from 11.3% to 22.6% for elective caesareans and 16% to 21.3% for emergency caesarean sections.

Graphs obtained from Public Health Scotland: Births in Scotland Year ending 31 March 2022

Nowadays the WHO 10-15% target is challenged in favour of a more individualised approach to evaluating caesarean section use. Death in pregnancy is an immeasurable loss which is devastating to the individual, their family and society. Sadly maternal mortality is only the tip of the iceberg. Beneath the surface of maternal mortality is the hidden weight of poor outcomes, harm, disability ( morbidity) and unsatisfactory experiences in pregnancy and birth that do not result in death. Evidence from the review of UK maternity services and outcomes in MBRRACE, Ockenden and Kirkup reports continue to remind us that listening to pregnant people is foundational to promoting safety, choice, respectful and person-centred care, all key ingredients for achieving high-quality maternity care. This can only be supported by maternity workforce training and safe staffing levels.

The Institute of Medicine defines quality as care that is patient/person-centred, safe, effective, efficient, equitable and delivered in a timely manner.

Shared decision-making is the goal.

As an obstetrician, I make recommendations for and against caesarean sections. I aim to make recommendations contextualised to the pregnant person, my clinical assessment, safety and logistical capacity. Some of my recommendations align with the pregnant person’s wishes, and some do not.

In the presence of capacity(the ability to use and understand information to make a decision and communicate any decision made), I believe that the ultimate decision on mode of birth should lie with the pregnant person supported by their birthing team using evidence-based, non-coercive counselling, which centres the views and needs of the pregnant person. Bodily autonomy is key. Occasionally balancing the bodily autonomy of a pregnant person alongside the needs of other service users in resource-limited settings ( fairness & justice) and their baby's well-being ( beneficence) can be extremely challenging, particularly in acute settings when there is evidence of sudden deterioration in maternal and newborn wellbeing. Ultimately we must strive to do no harm ( primum non nocere). Harm goes beyond the physical and acute- harm can be emotional, psychological and long-term( birth trauma).

As clinicians, we tend to focus on physical ( tangible) harm. Surely having a safe birth where the pregnant person and baby survive is enough? Compared to the average Scottish obstetrics and gynaecology registrar, I have witnessed more than the average share of maternal and newborn deaths and near misses whilst working in Nigeria and Uganda. It is truly devastating to everyone every time. According to United Nations agencies, globally, a woman dies in childbirth every two minutes. These are statistics we take seriously. And( not but), alongside a collective effort to reduce maternal and newborn mortality and morbidity, we must be equally committed to promoting positive birthing experiences for all pregnant people. We can do this by promoting shared decision-making during and after pregnancy and birth.

As users and providers of the service, we can facilitate choice and shared decision-making by asking or promoting discussion with these three questions:

What are my options?

What are the pros and cons of each option for me?

How do I get support to help me make a decision that is right for me?

“A systematic review for The Lancet’s Midwifery Series identified that women value not only appropriate clinical interventions but relevant, timely information and support so they can maintain dignity and control. Respectful application of evidence-based guidelines with attention to women’s individual, cultural, personal, and medical needs is essential for universal access to quality maternal care”

Language matters

The awe in my facial expression in the picture at the top of this blog is still how I feel at every birth I assist. It is very easy to forget that a standard day at work for us is the most significant day in someone else’s life. The language we use as obstetricians and midwives can be empowering or disempowering.

Babies are born by caesarean section, not delivered by caesarean section. I will never forget the wise words of one of my favourite consultant obstetricians, Dr Armstrong- “We deliver pizzas, not babies”. This is not just semantic OCD or excessive political correctness. The word delivery focuses on the birth attendant as opposed to the pregnant person who has done the bulk of the work-gestation, labour, and birth and will continue to work to care for that baby when our shift is over.

Good practice in birth communication. From BMJ Blogs Humanising birth: Does the language we use matter? by Natalie Mobbs, Catherine Williams, Andrew D Week.

I can empathise with pregnant people who may feel disheartened to have an emergency caesarean section after a long labour. One of the commonest reasons for a caesarean birth is when the birth canal does not dilate to 10cm. This can happen for many reasons-none of them are ever the fault of the pregnant person. But getting to whatever dilation, whatever the mode of birth, after several months of growing your baby and multiple hours of labour is something to be proud of. Yet multiple times, I have heard womxn in the UK, Nigeria, Uganda, and the USA share the guilt and belief that they “were not strong enough to push, or did not have the right pelvis for a natural birth, or failed at labour, or didn’t really give birth to their baby” because their baby was born by caesarean section. These feelings and guilt can be internalised and compound the experience of birth trauma and stigma. We contribute to this stigma by using words such as ‘delivered’ and ‘failure to progress’.

The stigma around caesarean section birth is a global phenomenon. The language we use as health professionals can help reduce these stigmas and in-power pregnant people to have positive, respectful and safe birthing experiences.

celebration: All births are valid

So to celebrate the end of caesarean section (CS) awareness month, I celebrate the validity of all births, including CS. I remember those who have died following CS as well as those who have survived because of CS. I celebrate those who support the safe provision of CS and those who nurse people who have undergone a CS. I am grateful to those who continue to advocate, implement policy and guidelines, and conduct participatory codesigned research, quality improvement projects, and audits around safe, positive and respectful birth.

You know who you are. I salute you!

For all pregnant people all over the world, no matter the mode or outcome of your birth, I share the same prayer that my African aunty shared with me this morning.

As you draw to a finish, recognise this is a new beginning. When your feet tire, may our spirit carry you over the line. May your enemies never see your path. You will live up to your name. You will not only finish well, but you must finish strong so that people behind you know it is possible and continue to aim for more.

To this, I hope your response will be, Isé( let it be so).

P.S. As always, if my thoughts this week struck a cord, piqued your interest, or you’d like to explore some of these ideas further or have questions, leave a comment and write to me HERE.

RESOURCES

Fivexmore: 6 steps to advocate for yourself for pregnant women and birthing people

Fivexmore: 5 steps for healthcare workers to reduce disparities in maternity care

Relationship between caesarean section rate and maternal and newborn mortality

Association of caesarean section with neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders of the off-spring